If you're new here, you may want to subscribe to my RSS feed. Thanks for visiting!

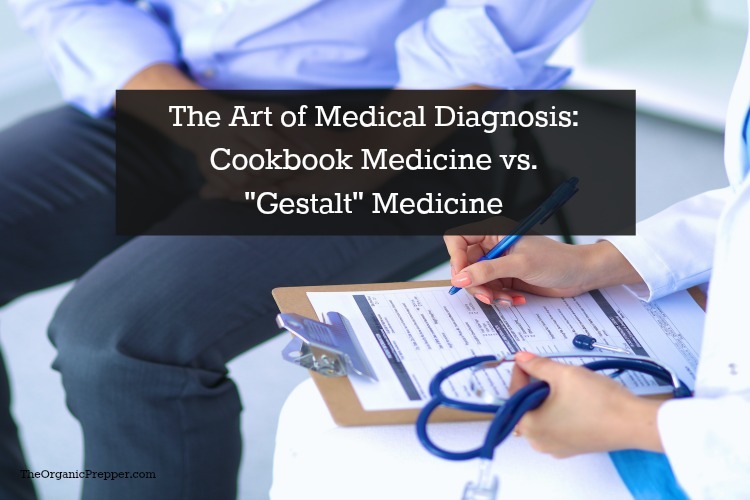

By BCE

I once suggested in an online forum that in an austere environment it was quite formulaic for a layperson to accurately diagnose a chest infection:

- Productive cough + fever = chest infection

- Shortness of breath / increased respiratory effort + fever = chest infection

- Sharp pain with breathing + fever = chest infection

- Low SpO2 (<90%) + fever = chest infection

Or, a combination of those symptoms and signs + fever = chest infection.

I was bombarded with several unexpectedly hostile responses and private messages saying what sort of crack-pot doctor was I and it could clearly be all sorts of other things and a quick Google search showed dozens of possible diagnoses for the symptoms I described and I typified lazy doctors and I should be ashamed of myself! A bit harsh, I thought!

Doctors use a method called clinical gestalt to diagnose patients.

Those guys had missed the point. Yes, medicine can be complicated, Yes, arriving at a diagnosis can be complicated. And, yes, a differential diagnosis list can be long. But making a solid educated guess is often relatively straightforward.

Most doctors and advanced practitioners use something called diagnostic reasoning to decide what is wrong with the patient. It utilizes a concept called clinical gestalt (making a decision based on the sum of your knowledge and experience) – it takes years and experience and it is why a simple computer algorithm hasn’t been able to replace humans in making a diagnosis and treating people…yet! The ability to look at all the information you have gained and apply your ‘gestalt’ to come up with the right diagnosis is the art of medicine.

Watching for patterns can help you diagnose illnesses.

But the bit that was missed in the original conversation was that I was talking about relatively inexperienced DIY medics coming up with a diagnosis that is probably correct and making some choices about what the problem was likely to be and if they needed to treat them or not based on learning/recognizing some simple patterns.

At its most basic, medicine is just complicated pattern recognition – to be honest some of it isn’t that complicated. Sometimes you make the diagnosis because you have seen the pattern before or you have read about the pattern. When you are relatively inexperienced in recognizing illness and making a diagnosis the first thing you need to master is simple pattern recognition.

The process can be applied to most common medical problems.

Take a urinary tract infection (UTI):

Young woman with pain when she urinates + going more frequently than normal + mild lower abdominal pain = likely UTI – it isn’t 100% certain, but you will be right 80-90% of the time

If you have access to basic tests like a urine dip-stick you can be more precise. The above case + presence of blood or white cells in the urine = almost 100% certainty a UTI.

Or cellulitis:

A patch of a red rash on a limb + it feels hot to touch + tender to touch + feels “woody” or firm to the touch + fever = likely cellulitis – not 100% but a novice will be right the majority of the time.

Sometimes, you’ll get the diagnosis wrong.

Basic diagnosis is pattern recognition. The problem with this approach is that you will be wrong sometimes – 1 in 5, maybe 1 in 10, maybe 1 in 20 or even 1 in 50 – but you will be wrong. This is the risk of the medic with limited training and experience undertaking diagnosis and treatment.

If this risk is acceptable or not depends on the situation. In a grid-up situation such as short term natural disaster then the risk of making an incorrect diagnosis and the consequences of that vs the benefit may simply not be there. But in a grid-down long term disaster with no access to medical care, it may be okay to only be correct in your diagnosis one in five times or one in ten.

The situation defines the level of risk you are prepared to take. This is where cookbook medicine very much has a role – it isn’t the ideal way to practice medicine, but it is a way.

While the purists often belittle the cookbook approach (and it isn’t by any stretch perfect) it is a good way for an amateur to begin to grasp what can be a difficult and complicated part of medicine, to the point they can provide useful care.

Learn to identify what normal looks like.

Going hand and hand with this approach is the important concept of knowing what normal looks like – if you know normal, you will be much more likely to recognize when something is abnormal or wrong.

Anatomy and physiology are the building blocks of medicine. These are some of the first courses that are taken at medical school. To understand when something is going wrong you need to understand how the body is put together and how it is supposed to work. The next step is mastering clinical examination which is built on your knowledge of anatomy and physiology – you don’t learn clinical examination until after you have learned how the body is supposed to look and how it is supposed to work. Having learned what normal is, clinical examination teaches you how to examine it for signs of abnormality.

Understanding this approach to assessing your patients is fundamental even when you don’t have extensive medical knowledge. The basics of human anatomy and physiology are easy to grasp for the lay medic – granted it gets complicated very quickly but a basic high school level of knowledge is really useful.

Then, learn to recognize what is NOT normal.

Identifying what is wrong with a patient is a case of knowing what is not normal. Recognizing that part of the body is not as it should be – either from a historical perspective or from an examination one.

The big question is how do you recognize that something is abnormal? The simple answer is that more normal you examine and look at, the more abnormal you are likely to be able to detect when it counts. Examine your significant other, your kids, your group, your friends. Take the time to look at a lot of normal and by knowing normal, the abnormal is more likely to stand out. There are lots of complicated clinical findings and for the inexperienced medic it can be very difficult to know exactly what it means – but knowing it isn’t normal and having the basic language to describe what is not normal is the first step to a more accurate diagnosis. It takes practice and time – but it can be done by the beginner.

About the Author

BCE is a Critical Care doctor who has 25 years’ experience in pre-hospital, remote and austere medicine. He has been a prepper/survivalist for even longer and pessimistically thinks a grid-down long-term collapse is not far away. He is passionate about improving medical knowledge within the prepper community and he is currently working on a book about truly primitive medicine and improvisation. He lives somewhere south of the equator on a Doomstead in a (hopefully) quiet isolated part of the world.

He helped write and edit the book “Survival and Austere Medicine” which is available for free download at https://www.ausprep.org/manuals and from a number of other sites and for purchase (at cost) from Lulu at http://www.lulu.com/shop/search.ep?contributorId=1550817

Questions, comments, and criticisms are welcome – post here and he will respond.

3 Responses

BCE;

Good article and spot on for most outpatient medicine.

I spent 30 years as a military ENT – 10 years of that running

a residency program. Pattern recognition and gestalt is a big

part of outpatient clinical medicine.

Thanks for the tip about ‘Survival and Austere Medicine’. I’ve

used wilderness / backpacking oriented e-books to bring along

on remote trips – haven’t thought to check out that particular niche.

r/

CMD

Excellent!

Very nice to read some common sense articles written by a person with extensive experience in evidence based medicine. I look forward to reading many more. You make some excellent points here.