If you're new here, you may want to subscribe to my RSS feed. Thanks for visiting!

By the author of Street Survivalism: A Practical Training Guide To Life In The City and The Ultimate Survival Gear Handbook

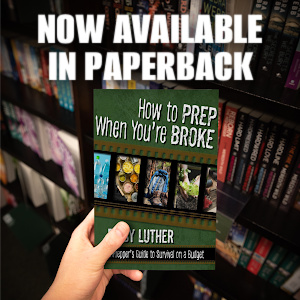

Around 100-150 years ago, the name “hobo” was used to describe a homeless or nomadic person, usually a man, who would hop on freight trains to get from place to place, often to find work. In the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, hobos were a well-known subculture, particularly during the Great Depression.

They wandered from town to town, searching for transitory employment, food, and shelter, leading a nomadic lifestyle. Even though they lived on the periphery of society, hobos upheld values that encouraged independence and respect for one another and the community they worked in.

Hobos were well-known for having a unique culture that included a code of conduct, symbols for communication, and even a yearly convention. The American traveling worker’s folklore has benefited from the songs and stories that hobos frequently wrote about their experiences. Their way of life has also been romanticized in literature, with some seeing it as a symbol of freedom and adventure. There are some interesting things that preppers and survivalists can learn from their lives.

Beyond their cultural and social relevance, hobos are also survivors – a good kind of survivor.

As one can imagine, life as a hobo was challenging and often involved dangers and hardships. However, it was a form of survival for many during a time of economic instability and job scarcity. Hobos didn’t survive on handouts. Instead, they relied on their resourcefulness, the help of their fellow travelers, and the communities they worked in.

In my Street Survival Book, I describe the homeless as “capable survivors.” Regardless of one’s opinion of them – and today, there are many different types of homeless – we must acknowledge the skill set necessary to live on the fringes of society, whether in a city or on the road. It’s something to behold.

Just as with the homeless, there are many different kinds of travelers: hobos, tramps, bums, the Roma, hippies, and so on. Most people consider these types to be connected, but they’re different: a hobo travels and is eager to work; a tramp has a reason to be on the road but tries to avoid employment. And a bum does neither: they stay fixed and rely on the support of others only.

The hobo is subject to the same challenges, hardships, and probations as everyone living on the streets or the road. However, they can be considered unique because of their origins, their history, and, above all, their ethics. Those things make all the difference. Traveling from town to town as a decent person was much easier than a vagrant. Likewise, it’s a lot easier to live in the streets as a decent person.

Also, in my book, I highlighted how decent conduct can impact the standard of living and quality of life of someone living on the streets. After years of trying that lifestyle myself and getting in contact with all kinds of street people, I can affirm that living by the code of the hobo is a superior – much better, safer, and healthier – way than being a bum or worse, an outcast, involved with drugs, alcohol, and crime.

The history of the hobo

Although there are several variations and unclear origins, the name first appeared in the American West around 1890. Some claim it was a shorthand for “homeless boy” or “homeward bound.” Others claim that after the war, Confederate veterans of the Civil War were destitute, impoverished, and hungry, and some even strolled through towns looking for work while carrying a garden hoe. Author and journalist Bill Bryson wrote many nonfiction books on topics in American culture. In his 1998 book “Made In America,” he suggests that the term “hobo” might have originated from the train salutation “Ho, beau!”

By the late 19th century, the heart of Hobohemia was the main drag in Chicago, where train lines radiated out into every corner of America. It was easy to find work in the slaughterhouses, to go west and build a dam, or go east and take a job in a new steel mill to make a buck before you caught the road again.

The hobo would follow the boom-and-bust movements of a shifting economy, searching for transient work like lumbering and mining or seasonal fruit picking in parts of the country without much population, where more hands were needed. That’s how railroads and hobos became integral to the US labor movement, especially in the Pacific Northwest.

The hobo subculture of the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries has parallels with the “Beat Generation” of the 1950s. Both embraced alternative lifestyles and values that challenged mainstream norms. The Beat Generation celebrated nonconformity, spontaneity, and a nomadic lifestyle, much like the hobos before them.

The Beats also traveled across the US, often by hitchhiking or hopping freight trains, searching for personal discovery and broader cultural engagement. Their movement laid the groundwork for the countercultural revolutions of the 1960s, such as the hippies.

A unique period of American history is reflected in the hobo ethical code.

The Hobo Code – an outline of ethical practice and communal etiquette for those living a transient lifestyle – was written in Chicago in 1894 and introduced during the 1889 National Hobo Convention held in St. Louis, Missouri.

Based on mutualism and self-respect, it remains every hobo’s founding document, a simple and forthright set of instructions to live by. It’s a fascinating study in nomadic social order and serves as a reminder that every subculture has customs and guidelines that set expectations for conduct and guarantee the well-being of all participants.

Despite the difficulties of a nomadic lifestyle, the tenets outlined demonstrate a strong sense of camaraderie and respect among hobos and a focus on individual accountability and dignity. The code emphasizes the value of honoring the law, the environment, and the towns they travel through.

THE HOBO CODE

- Decide your own life; don’t let another person run or rule you.

- When in town, always respect the local law and officials, and try to be a gentleman at all times.

- Don’t take advantage of someone who is in a vulnerable situation, locals, or other hobos.

- Always try to find work, even if temporary, and always seek out jobs nobody wants. By doing so, you not only help a business along but ensure employment should you return to that town again.

- When no employment is available, make your own work by using your added talents at crafts.

- Do not allow yourself to become a stupid drunk and set a bad example for the locals’ treatment of other hobos.

- When wandering in town, respect handouts and do not wear them out; another hobo will be coming along who will need them as badly, if not worse than you.

- Always respect nature; do not leave garbage where you are wandering.

- If in a community jungle, always pitch in and help.

- Try to stay clean and boil up wherever possible.

- When traveling, ride your train respectfully. Take no personal chances, cause no problems with the operating crew or host railroad, and act like an extra crew member.

- Do not cause problems in a train yard; another hobo will be coming along who will need passage through that yard.

- Do not allow other hobos to molest children; expose all molesters to authorities – they are the worst garbage to infest any society.

- Help all runaway children and try to induce them to return home.

- Help your fellow hobos whenever and wherever needed; you may need their help someday.

- If present at a hobo court and you have testimony, give it. Whether for or against the accused, your voice counts!

The hobo tradition and lifestyle lives on.

The hobos still have a National Hobo Convention, held on the second weekend of every August since 1900 in the town of Britt, Iowa. It’s organized by the local Chamber of Commerce and known throughout the town as the annual “Hobo Day” celebration. It’s the largest gathering of hobos, rail-riders, and tramps, who gather to celebrate the American traveling worker.

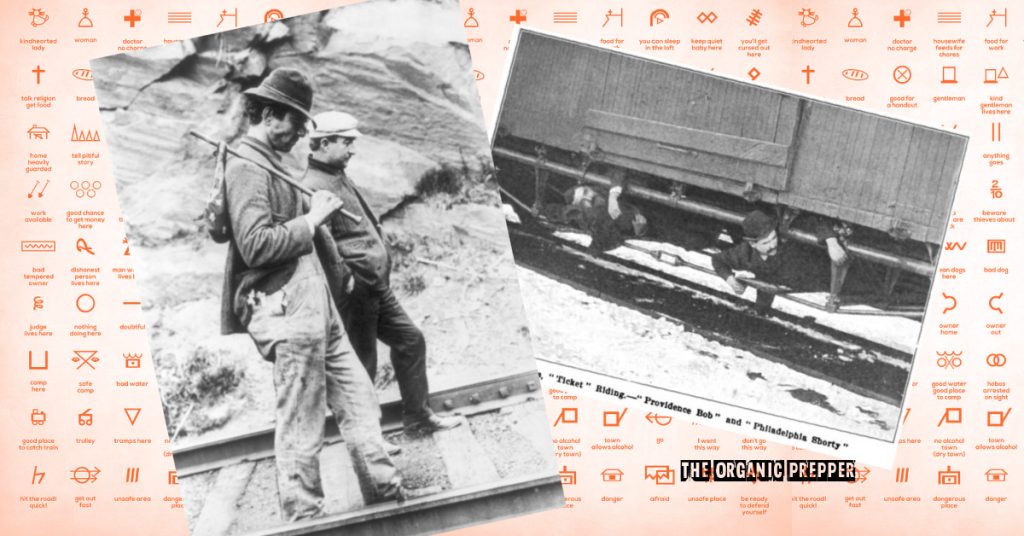

The Symbols

The exclusive, secret language based on symbols to communicate with other hobos coming to town about threats, opportunities, and lots more, reveals how sophisticated and established is the hobo culture. That alone separates them from any other kind of wanderer or street type and is in no small part responsible for the enduring tradition of the hobo.

“This brilliant, hieroglyphic-like language appeared random enough for busy people to ignore, but perfectly distinctive for hobos to translate. The code assigned circles and arrows for general directions like, where to find a meal or the best place to camp. Hashtags signaled danger ahead, like bad water or an inhospitable town.” [SOURCE]

A similar strategy is used by people in various SHTF, from wars to invasions, and even among trekkers and backpackers. Sometimes it’s more discreet (for OPSEC reasons), others it’s more open. But the principle remains, and it’s another unique facet of the hobo culture.

Final words.

I’m a common citizen with family, friends, work, and a home. However, between my passion for trekking, backpacking, and camping in wild and rural settings, my days and nights in the streets among the homeless, I confess to have an attraction to the nomadic, independent lifestyle. Maybe that’s why I keep going away from time to time.

I also have a passion for history, and find the hobo a fascinating part of American culture. They exist in many, if not most, other countries as well, and their incredible stories are accounts of a different era, reflecting wisdom, tradition, and the true spirit of survivalism.

For further reference, here are some books that can be found on Amazon and other outlets.

The Hobo: The Sociology of the Homeless Man, by Nels Anderson and Robert E. Park

The Autobiography Of a Super Tramp: The Life of William Henry Davies, by W. H. Davies

The Road, by Jack London

The hobo lifestyle, code of conduct, work-based ethics, and system of communication were all forged in practice during a very hard and challenging period, which means it’s proven to work and thus can provide valuable lessons for crises and other SHTFs.

Do you know of any other lessons we can take from the hobo subculture? Do you have any stories about hobos to share? Let’s discuss it in the comments section.

About Fabian

Fabian Ommar is a 50-year-old middle-class worker living in São Paulo, Brazil. Far from being the super-tactical or highly trained military survivor type, he is the average joe who since his youth has been involved with self-reliance and outdoor activities and the practical side of balancing life between a big city and rural/wilderness settings. Since the 2008 world economic crisis, he has been training and helping others in his area to become better prepared for the “constant, slow-burning SHTF” of living in a 3rd world country.

Fabian’s ebook, Street Survivalism: A Practical Training Guide To Life In The City , is a practical training method for common city dwellers based on the lifestyle of the homeless (real-life survivors) to be more psychologically, mentally, and physically prepared to deal with the harsh reality of the streets during normal or difficult times. He’s also the author of The Ultimate Survival Gear Handbook.

You can follow Fabian on Instagram @stoicsurvivor

7 Responses

interesting subject, enjoyed it! too bad all the ILLEGALs dont follow the decent code…..

Yes, but they pay the price believe me. In the streets (and life in general), we do what we must, and that makes a difference both to ourselves and those around us.

Stay safe, stay hobo!

Fascinating article. Love the code of conduct and symbols.

My grandfather was a hobo out of St. Louis. Enjoying the symbols and their code of ethics.

I interviewed an elderly neighbor lady years ago for a high school project. The subject was the Great Depression. She talked of feeding hobos, letting them sleep in the barn in exchange for farm work. It was the first I’d ever heard of hobos making it to the rural area of South Dakota! Sure wish I’d paid more attention to the stories and knowledge of those people who are now long gone.

John Steinbeck wrote a couple of really good books that touched on this . “ Grapes of Wrath “ and “Of Mice and Men “ .

My great grandparents lived on a farm. I am told that hobos would regularly show up for Sunday dinner and were never turned away. It was certainly a different time.